Fountains Abbey is one of the most glorious remnants

of medieval Cistercian monasticism in England, and was

once one of the wealthiest abbeys in medieval Europe.

The Cistercians

|

|

Bernard of Clairvaux

|

The Cistercian Order spread very rapidly from its humble beginnings in 1098, when Robert of Molesme and several companions left the Benedictine community of Molesme in search of a more ascetic lifestyle through observance of a more literal obedience to the

Rule of St. Benedict

. They traveled to "a howling wasteland," Cîiteaux, France, and founded a new community, which they named the

novum monasterium.

They gradually began to attract others to their movement, including the Burgundian noble,

Bernard of Clairvaux

. It was Bernard's entrance which began to fuel the growth of what became the

Cistercian Order

, which had some 300 daughter houses by the end of the twelfth century. All houses were governed by the

Carta Caritatis

, which mandated a white habit of coarse wool, giving rise to the description of the Cistercians as the White Monks, in contrast to traditional Benedictines, known as the Black Monks. Just as the coarse, undyed wool helped to turn the monk away from the pleasures of the senses, so too the direction to eat only the coarsest wheat bread, and to avoid colored glass in the chapel, gold and silver on the altar was also intended to keep the monks focused on the spiritual life of prayer, governed by the Benedictine Rule.

Return to Index

Cistercian Ideals

The Cistercians believed that they were returning to the original spirit and letter of the Rule of St. Benedict, which had been corrupted by contemporary monastic life. Bernard described the riches and splendor of Cluny as being in a "den of thieves," and Cistercians argued that the Cluniacs had forgotten Benedict's direction on manual labor, as they focused so large a portion of their day on liturgial practices. Cistercians reinvigorated the ideal of manual labor, following Benedict's statement that "idleness is the enemy of the soul" (RB 48:1). The Rule of Benedict also tied manual labor to prayer, enjoining the monastic to "regard all ... goods of the monastery as sacred vessels of the altar" (RB 31:10); one's work, therefore, was a reflection of one's prayer, and prayer a reflection of work. This emphasis on manual labor had an important effect on the development of Europe. The Cistercians deliberately founded their communities in wastelands, remote from centers of population. Their zeal for manual labor resulted in the rejuvenation of Germany's frontiers, as well as the wastelands of northern England, pillaged by the Normans and danes before. They developed new species of apples, became important producers of wine in Europe and wool in England, and excelled in animal husbandry. It has been said that "all the world threatened to become Cîteaux" (Knowles,

Monastic Order in England

, 224), a reflection of the impact the Cistercian monastic life had on the development of Europe.

Return to Index

Cistercians Found Rievaulx and inspire a crisis at St. Mary's Abbey in York

The rapid growth of the Cistercian Order and the zeal for

religious life that marked the twelfth century eventually

propelled its monks to England. The Cistercians founded

their first house in England at

Rievaulx (link not yet functional)

, north of York.

|

As they travelled through the countryside, their

obvious zeal and renewed vision of monastic life

attracted the attention of other communities,

including that of St. Mary's of York, a Benedictine

house. St. Mary's was then in a state of

decline, and was led by an elderly abbot.

Following the visit of the White Monks in

1132, the Prior of St. Mary's, Richard,

presented a petition to the abbot calling for

the reform of the community along Cistercian

lines. The abbot denied the proposal, and

tension increased until the Archbishop,

Thurston, was called in the resolve the

dispute. As the situation became ever more perilous

for the thirteen dissidents led by Prior Richard, he

was forced to take them into his protection.

Return to Index

|

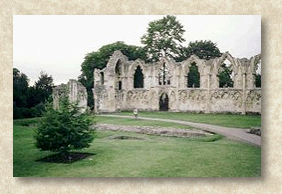

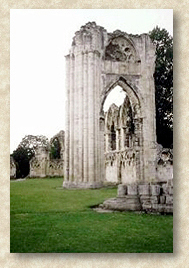

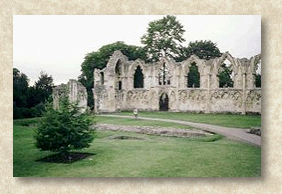

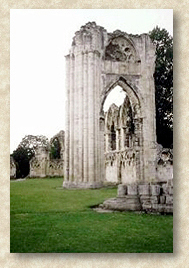

Ruins of

St. Mary's Abbey, York

|

St. Mary's

|

|

copyright © Dr. Deborah Vess 1995. All rights reserved.

For further information regarding these materials, contact the author via e-mail:

dvess@mail.gcsu.edu

dvess@mail.gcsu.edu

or by snail mail at:

Dr. Deborah Vess

Director of

Interdisciplinary Studies

and Associate Professor of History

Georgia College & State University

CBX 048

Milledgeville, Georgia 31061-0490

A very special thanks to Cathy G. Locks, graduate assistant in Interdisciplinary Studies and graduate student in history for technical assistance.

|

|